“My God, what have we done?” —Log entry by the copilot of the Enola Gay, August 6, 1945, on watching the city of Hiroshima disappear under the mushroom cloud of the first atomic bomb

Through personal stories, creating educational campaigns based on their own experience and issuing urgent warnings against the spread and use of nuclear weapons, the survivors—or hibakusha in Japanese—have spread awareness of the apocalyptic effects of nuclear weapons and have brought about widespread opposition to them.

In presenting the award, the Nobel Committee stated, “The hibakusha help us to describe the indescribable, to think the unthinkable and to somehow grasp the incomprehensible pain and suffering caused by nuclear weapons.

“The extraordinary efforts of Nihon Hidankyo and other representatives of the hibakusha have contributed greatly to the establishment of the nuclear taboo. It is therefore alarming that today this taboo against the use of nuclear weapons is under pressure.”

“Humanity must never again inflict nor suffer the sacrifice and torture we have experienced.”

That pressure is occurring on several fronts. The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) reported this year that the nine nuclear-armed nations “continued to modernize their nuclear arsenals and several deployed new nuclear-armed or nuclear-capable weapon systems in 2023.” SIPRI estimates that, as of early 2024, there are 12,121 nuclear warheads across the globe, about 9,585 of which are ready for immediate use.

World leaders who cling to their nuclear weapons possibly understand that war is the conversation of hate, but can’t or won’t understand that nuclear war silences that conversation and all other conversations forever.

Eleven years after the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the hibakusha of the newly formed Nihon Hidankyo published a “Message to the World”: “Up until now, we have kept our silence, hid our faces, scattered ourselves and led our lives that were left to us. But now, unable to keep our mouths shut, we are rising up,” the message read.

“On behalf of the soundless voices of the people who died a miserable death at the moment of the bombing, of those who died of horrible A-bomb disease, of over 300,000 fathers and mothers, sons and daughters, husbands and wives.” It continued, “we appeal to the world uniting our voices. Humanity must never again inflict nor suffer the sacrifice and torture we have experienced. We are determined not to hold our tongues anymore, whatever force and authority we have to challenge.”

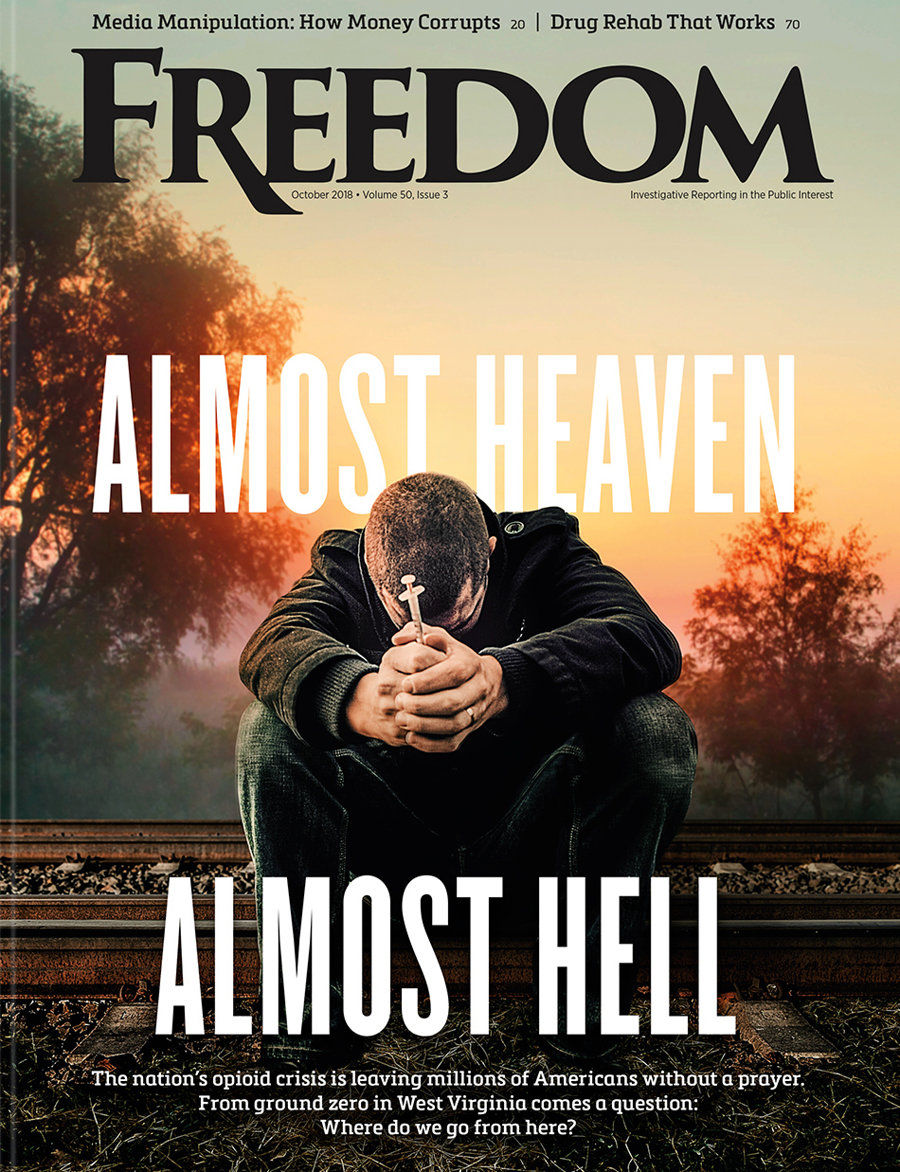

The surviving hibakusha—most of whom were small children in 1945—are dying off, and with their passing, their living testimony passes as well. But they are the survivors of the only nuclear weapons detonated in the name of war. There are, however, many thousands more enduring a tortured existence from later, far more powerful weapons unleashed, at least allegedly, in the name of peace.

A recent UN human rights report details 67 nuclear tests detonated in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific from 1946 to 1958 involving bombs, each of which packed 1,000 times the destructive force of those dropped in August 1945. The islanders who evacuated to nearby islands were blanketed with as much radiation as 1.6 Hiroshima bombings every day for 12 years.

The result for the nearly 40,000 inhabitants and their descendants? Living hell. Thyroid tumors, stillbirths, eye problems, liver cancers, stomach cancers and leukemia. Mothers watching as their children’s “hair fell to the ground and blisters devoured their bodies overnight.” The eyewitness descriptions of the births of what the islanders call “apples” or “turtles” or “octopuses,” because there are no words in their language to describe them; of “jellyfish” babies without bones, yet somehow still alive and breathing, only to die after hours of unimaginable suffering—these accounts are difficult to read without experiencing waves of nausea.

US Commander Ben Wyatt, in instructing the islanders to evacuate, assured them that the nuclear testing was for “the good of mankind and to end all world wars.” Very likely Commander Wyatt believed his own words. It was and still is the rationale that “peace” would come through mutually assured destruction. That nuclear weapons in the hands of enough nations would deter the use of nuclear weapons.

As recently as last year, the Group of Seven (G7), an international gathering of the seven nations with the largest advanced economies, released a statement urging that nuclear weapons “for as long as they exist, should serve defensive purposes, deter aggression and prevent war and coercion.” Not a word about disarmament.

As Alfred Nobel—founder of the Nobel Prizes and inventor of dynamite, the most destructive weapon devised by man at the time—wrote in 1891: “On the day that two army corps can mutually annihilate each other in a second, all civilized nations will surely recoil with horror and disband their troops.”

Escalating and expanding nuclear armament as a “deterrent,” in other words, depends on mutual distrust.

Nuclear disarmament, on the other hand, depends on mutual trust.

As Scientology Founder L. Ron Hubbard wrote, “On the day when we can fully trust each other, there will be peace on Earth.”

Which “On the day” will it be?

Nobel’s day of mutual distrust and fear, or Mr. Hubbard’s day of mutual trust and hope?

The answer to that question depends on you and me—and everyone else.