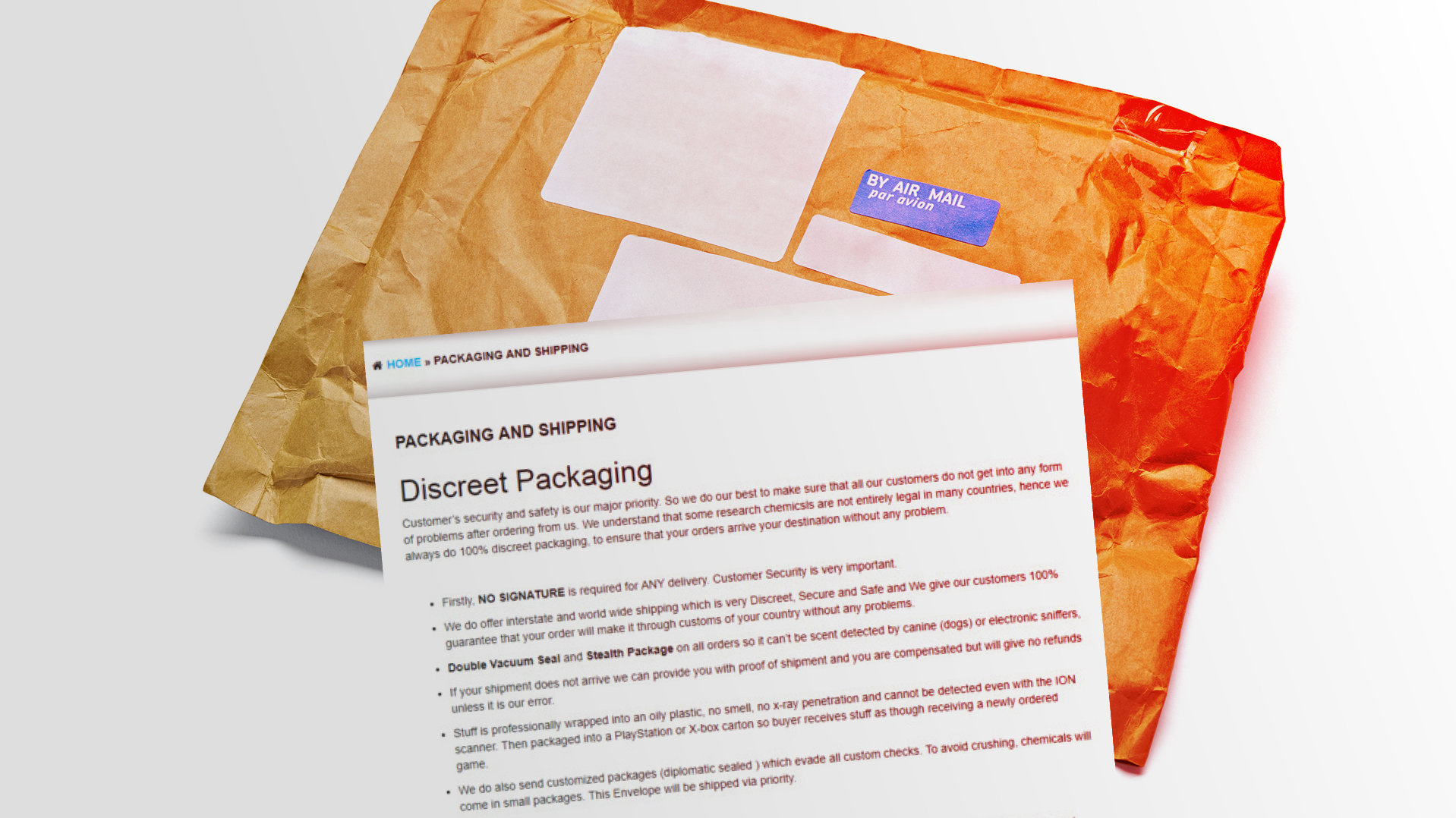

Both the Postal Service and State Department have turned down requests to require electronic shipping information containing the names and addresses of the shippers and the receivers of these deadly international parcels. Citing logistical and foreign relations reasons for failing to police the incoming drug traffic, the government agencies now face a new investigation by Portman’s subcommittee.

The initial investigation used Google to search websites offering synthetic opioids, which led—according to one investigator—to “hundreds of pages offering the stuff for sale.” The investigators posed as first-time buyers and found six sellers offering fentanyl, which is the top source of accidental deaths in Ohio. When investigators pretended to hesitate, the sellers offered “flash sales” and discounts, even trying to “upsell” carfentanyl—which is 100 times more powerful than fentanyl, according to authorities.

Virtually every type of payment option was offered by the sellers, from Bitcoin to pre-paid gift cards. Although no purchases were made, investigators harvested payment and transaction records via congressional subpoena power over Western Union and other money transfer agencies.

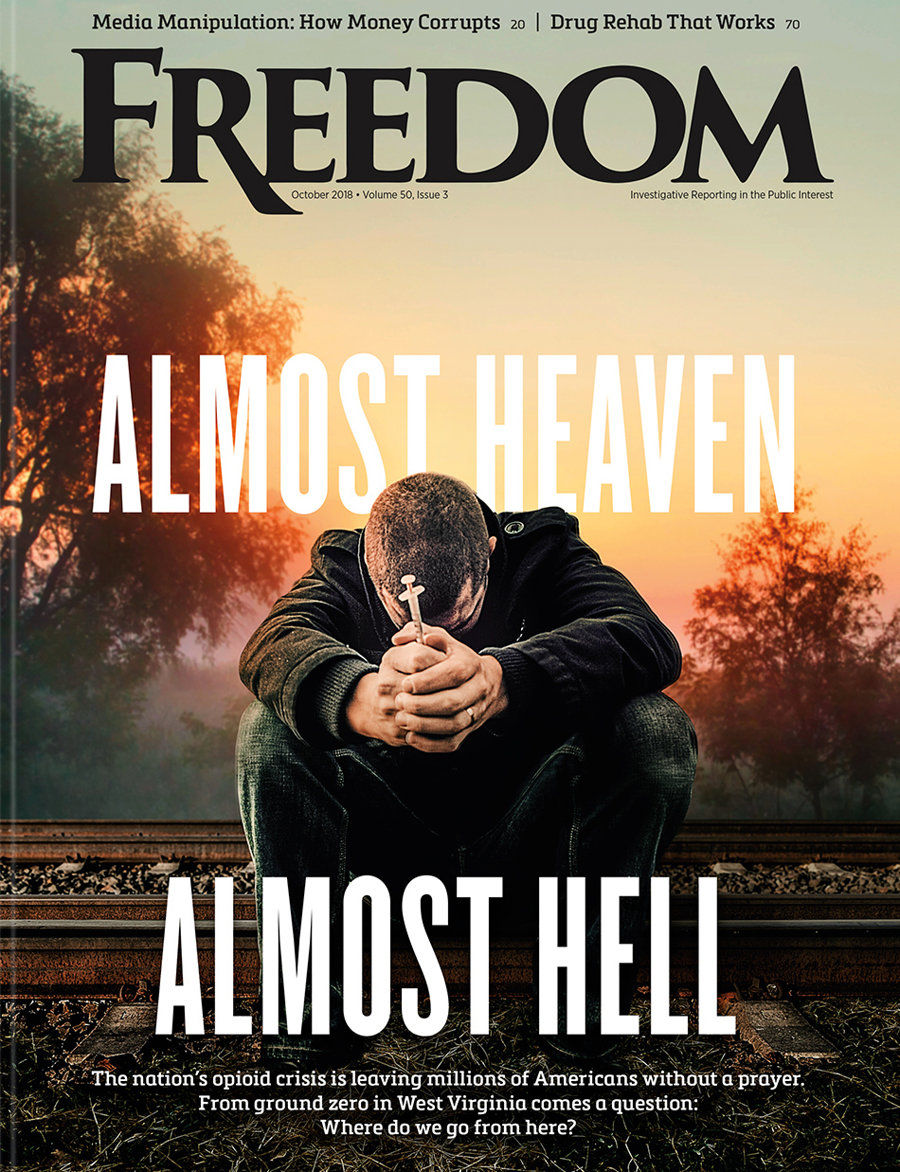

The records revealed that the six contacted sellers made more than 500 financial transactions with more than 300 buyers in 43 states, for a total of $230,000 in sales. The shipments usually came from China, though some went to an intermediary in Europe before being reshipped to the U.S.

Using payment services information, investigators learned the identities of some of the buyers—18 of whom were arrested. Another seven buyers were identified through obituaries after having died from fentanyl-related overdoses.

Although the subcommittee members condemn the drug trade, they have put the Postal Service in their sights because they have jurisdiction over it. Private services like FedEx, UPS and DHL operate under congressional order to collect names and addresses of all who ship or receive a package. But the Postal Service, with its much higher shipment volume, is not covered by that legislation.

This has been a recipe for disaster, as the volume of potentially illegal shipments has grown. Between 2013 and 2017, the volume of inbound international mail grew by 232 percent.