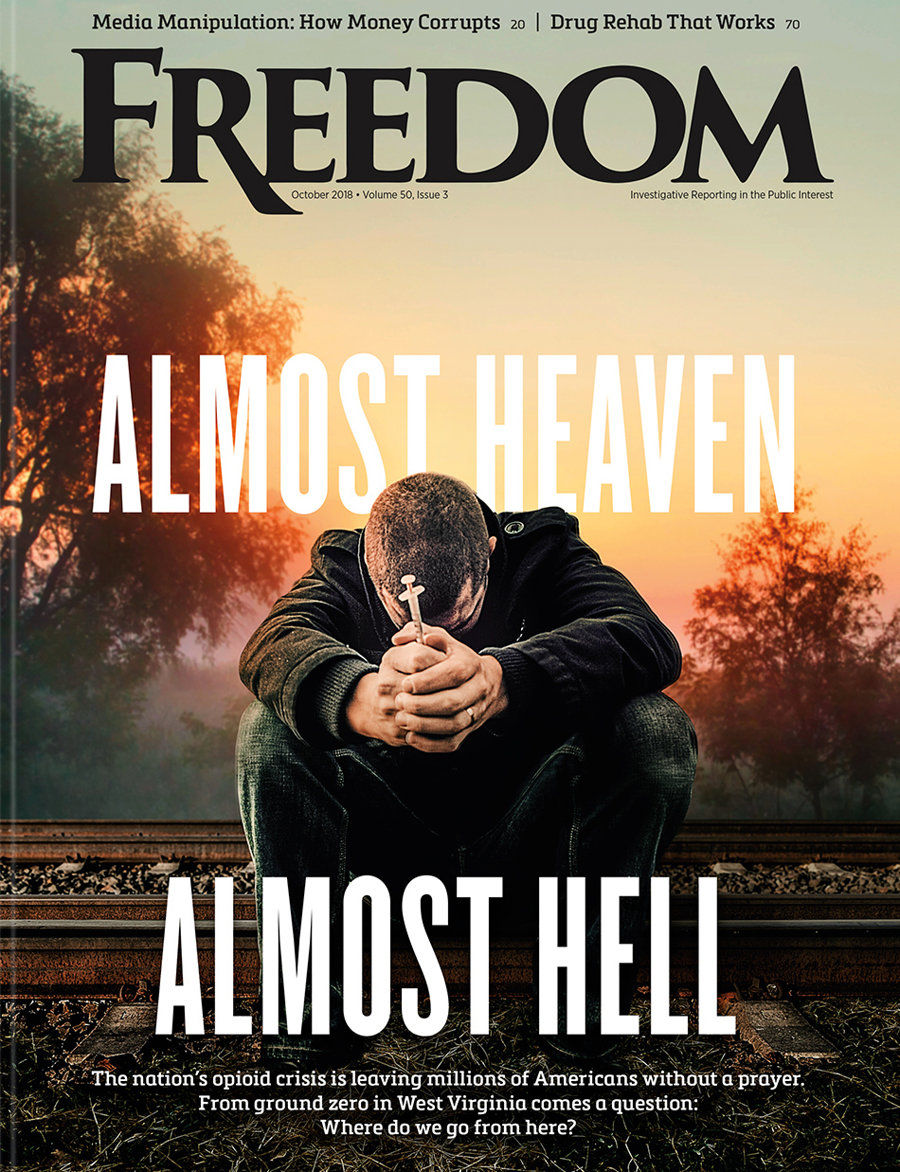

Psychedelics have a worrisome history of misuse and abuse in which drug companies and mental health practitioners alike have played diabolical roles. Yet these same players have swept aside old inconvenient truths in their frenzy to cash in and get these drugs into the marketplace.

The sordid saga of psychedelics dates back at least to 1954, when British writer Aldous Huxley published his bestselling book The Doors of Perception, an autobiographical work in which he extolled the virtues of mind-altering “mystical” drugs, thereby influencing not just the popular perception toward them but also the direction of hallucinogenic drug research. It was shortly after his endorsement of psychedelics that Swiss drugmaker Sandoz began distributing LSD to psychiatrists.

“Their internal trials of the drug had left them unsure of what diagnoses it should be indicated for, and in what doses; their solution was to offer it free to psychiatrists on an experimental basis, in return for their clinical recommendations,” writes medical historian Mike Jay in his 2023 book Psychonauts: Drugs and the Making of the Modern Mind.

“In 1959, before Timothy Leary had taken his first mushroom trip,” writes Jay—referring to the Harvard psychologist who promoted psychedelic drugs and urged America’s youth to “turn on, tune in, drop out”—Hollywood heartthrob “Cary Grant stood on the set of his film-in-progress ‘Operation Petticoat’ and announced to the press—and to the horror of his studio publicists—that LSD therapy with Dr. Janiger had changed his life.”

Los Angeles psychotherapist Oscar Janiger was among those who accepted the Sandoz offer, and his celebrity clients played a crucial role in promoting LSD to a wider audience.

“In 1959, before Timothy Leary had taken his first mushroom trip,” writes Jay—referring to the Harvard psychologist who promoted psychedelic drugs and urged America’s youth to “turn on, tune in, drop out”—Hollywood heartthrob “Cary Grant stood on the set of his film-in-progress Operation Petticoat and announced to the press—and to the horror of his studio publicists—that LSD therapy with Dr. Janiger had changed his life.”

But Grant’s rosy report of his experience with LSD did not match the experiences of several renowned European intellectuals who a quarter-century earlier had experimented with psychedelics. One for one, their experiments with the psychedelic drug mescaline quickly devolved into bad trips that haunted them for weeks.

Perhaps the best-known incident involved the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre, who claimed that his 1933 encounter with mescaline in Paris almost drove him to a nervous breakdown.

“After I took mescaline, I started seeing crabs around me all the time,” he recalled. “I mean they followed me into the street, into class.” Although Sartre realized he was imagining the crustaceans, “he spoke to them, requesting them to be quiet during his lectures,” Jay wrote in a 2019 article in The Paris Review.

Alluding to “claims of uncritical positive regard and hype,” the study points out that because psychedelics are much more widely used outside research settings, “the emphasis on positive outcomes in controlled studies may present a misleadingly, over-generalized positive picture of the effects of psychedelics.”

Eight months before psychedelics overpowered Sartre’s mind, the German philosopher Walter Benjamin was administered mescaline in Berlin by psychiatrist Fritz Fränkel who was codirecting a study on the psychology of addiction.

The drug appeared to make Benjamin restless and irritable. It also made him shiver. “In shuddering, the skin imitates the meshwork of a net,” he later recalled. “But the net is the world net: the whole universe is caught in it.”

Now, nearly a century later, much of the mental health research world is focused on promoting psychedelics as if they were the latest miracle cure in the field.

A September 2023 study by Imperial College, London, one of the pioneering research institutions in psychedelics, warned of the substantial risk of psychedelics for individuals with preexisting mental health conditions or a history of psychosis.

Alluding to “claims of uncritical positive regard and hype,” the study points out that because psychedelics are much more widely used outside research settings, “the emphasis on positive outcomes in controlled studies may present a misleadingly, over-generalized positive picture of the effects of psychedelics.”

In other words, the hype is not borne out by the study’s research.

Titled “Case Analysis of Long-Term Negative Psychological Responses to Psychedelics,” the study recruited volunteers through social media ads. They “reported experiencing negative psychological responses to psychedelics” for more than 72 hours after using the drugs, which included MDMA (ecstasy) and other “classical psychedelics” such as psilocybin, mescaline (derived from the peyote cactus) and Ayahuasca (a South American tea brewed from certain botanicals).

Of the volunteers, 32 responded to a detailed questionnaire and underwent a psychiatric diagnosis following their psychedelic experience, according to the study, which reported that anxiety symptoms surfaced or worsened in 87 percent of the respondents.

Of the volunteers, 32 responded to a detailed questionnaire and underwent a psychiatric diagnosis following their psychedelic experience, according to the study, which reported that anxiety symptoms surfaced or worsened in 87 percent of the respondents.

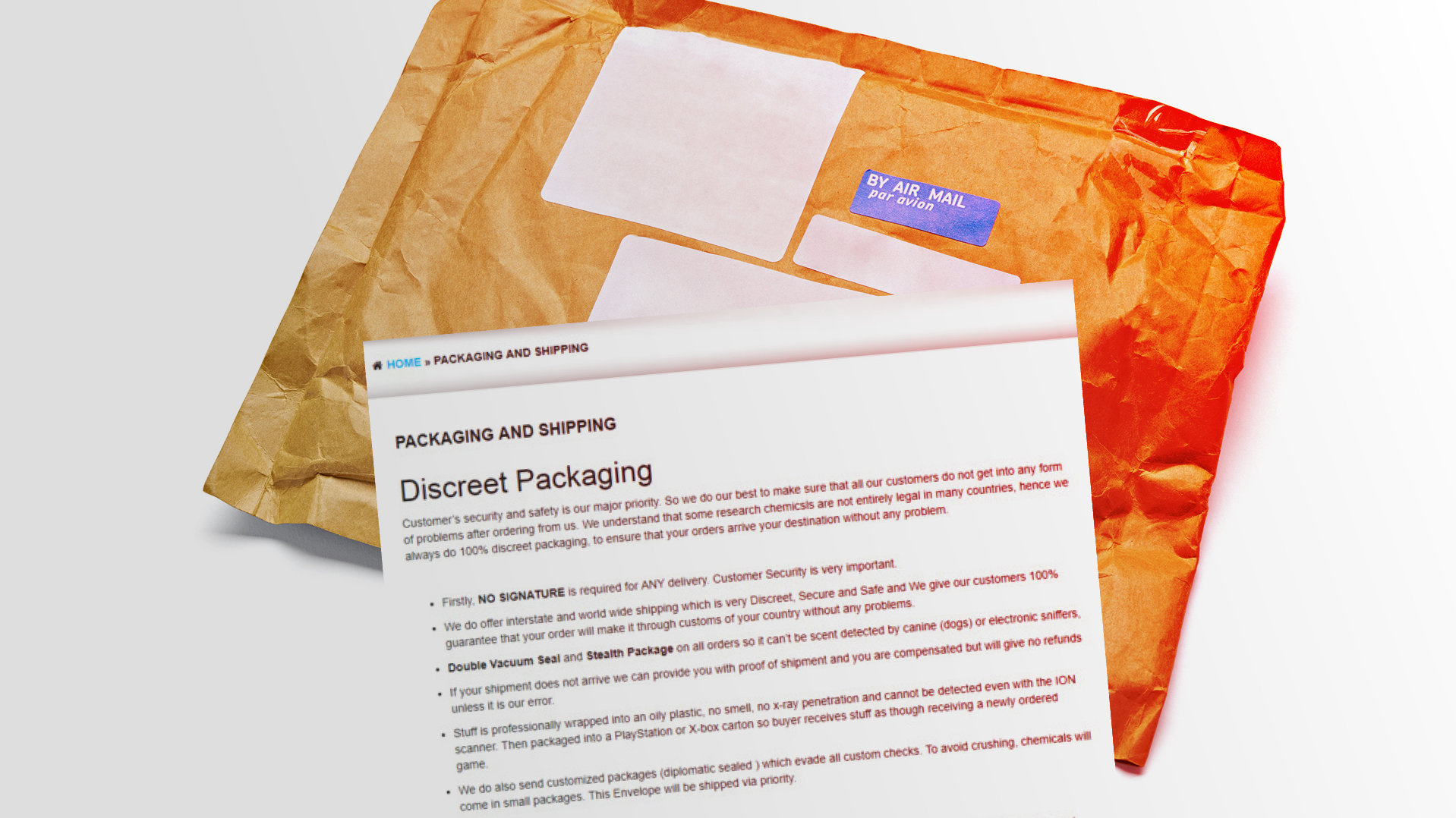

“There is a growing global industry of illegal, semi-legal and fully legal psychedelic retreats and care services, particularly in Europe and the Americas,” the study reported. “Moreover, evidence suggests that an increasing number of individuals struggling with mental health conditions are seeking to self-medicate with psychedelics and epidemiological data suggests a sizable increase in the prevalence of psychedelic use in the last 15 years.”

While psychiatrists may continue to champion psychedelics as a panacea for mental health woes, studies such as this show the pitfalls of believing the hype. The reality of psychedelics is that they are drugs and as such, they are poisons. And while drugs have their uses in medicinal remedies based on evidence-based trials, actual reviews of using psychedelics for mental health conditions show they, like other psychiatric drugs, cure nothing and, in the long term, offer worsened symptoms.

Understanding the disparity between mental health industry claims and the actual effectiveness of psychedelics is the crux of the matter when they are touted as psychiatry’s latest pharmaceutical “solution.” The answer to why psychiatry is pushing psychedelics lies in following the money.

The series continues with Part III: The Truth About Psychedelic Drugs