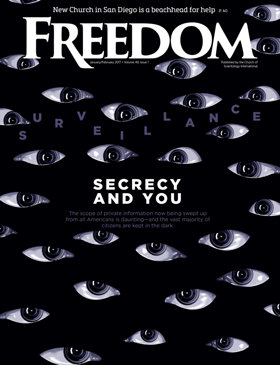

How to watch everyone without being watched—that’s the lust of every dictator, authoritarian, totalitarian, social manipulator and corporate voyeur. Many despotic endeavors have ascended and collapsed based mostly on their ability to spy on citizens.

The Church of Scientology, since its founding in the mid-twentieth century, has been a champion of civil rights, privacy and open government.

Freedom, the voice of the Church since 1968, has carried forward this mission.

In this issue, we pursue the dual quests for openness in government and the rights of citizens to be safe from all forms of official and corporate spying.

Even the ancient Greeks mused about what we now call the “surveillance state.” Argus Panoptes (aka “all seeing”) was a watchful giant with a hundred eyes.

In the late 18th century, British philosopher Jeremy Bentham conceived of a useful architectural scheme for snooping on convicts. It was called, in honor of the very optically endowed Hellenic giant, the Panopticon—a circular structure in which a single jailer could monitor prisoners without the inmates knowing they were being watched. The induced paranoia was calculated to reform criminals, or as Bentham noted, to create the “power of mind over mind.”

“Mind over mind” is the aspiration, the Holy Grail, of every totalitarian. In George Orwell’s 1984, a technological variation on the Panopticon, the two-way “telescreen,” ensured that citizens’ “every movement [was] scrutinized.” The chilling words emanating from the telescreens announced to exposed perps: “You are the dead.”

Technology has moved far beyond 1984—in both Orwellian and real time. The ever-watching eye of Big Brother is now encoded in gazillions of zeros and ones. Your computer, the ubiquitous cell phones and tablets, those Google ads that seem to know exactly what you were thinking of buying, the closed-circuit TV, the feeds from the camera on that drone you gave your kids for the holidays, the cop drones that will soon buzz across our cities’ skies (if they already aren’t doing so)—all information is everywhere all the time.

And someone is perusing that data. Sifting them. Combing them. Deciding if you might be a terrorist, a run-of-the-mill crook, or—what officialdom fears most—someone suspected of, as Orwell intoned, “thought crime.”

There’s an old joke about a guy at an airport who sees a friend and shouts, “Hi, Jack!” Security guards immediately pummel the guy to the ground, thinking he planned to hijack a plane. That joke has a modern expression. Algorithms scurrying around massive computer complexes try to ferret out people who are guilty—or are just perceived as guilty. Maybe a kid writing a term paper on the ancient Egyptian goddess Isis attracts the attention of a gargantuan computer—and as quick as an electron can whirl around a proton, that child is flagged along with some really, really bad actors connected to another ISIS.

The federal government and its hundreds of eager, well-paid corporate contractors watch and watch and watch: You. They collect. They know where you are, who you talk to, what you view online, what you write and record. Everything the spooks do to learn your secrets is itself a secret you’re not supposed to know.

You are told that if you’re not doing anything wrong, don’t worry about the snooping. And if you believe that, you have no understanding of history. American officials have used such surveillance to undermine and subvert the legitimate activities of citizens. From the dossiers on Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., to the criminal activities of agent provocateurs to disrupt peaceful protests, to the illegal spying on law-abiding citizens for no reason other than officials’ prurient curiosity, the government’s intelligence masters have used their apparatus in ways that would horrify the men who crafted the U.S. Constitution.

In our cover story, “The Data Demon” by Mark A. Taylor and Ajay Singh, we reveal the National Security Agency’s monstrous computer complex in Salt Lake City, and dig into threats posed to all Americans.

In a second feature, we deal with another genre of abuse. James Richardson, a poor black man in Florida, was wrongly accused of killing his own children, then spent years on death row—the victim of trenchant racism in the South.

Our reporter, Peter Gallagher, wrote the stories that were instrumental in exonerating Richardson and securing his freedom. Yet it is only recently that Richardson finally started to receive the compensation he was due from the state, decades after his release.

We also cover a different side of freedom altogether—one which prevailed in San Diego, California, when a new Church of Scientology opened to uplift lives and communities countywide.

In our “Into the Field” section, we then trek from South Los Angeles to the United Kingdom, to Ukraine and Kenya, on the trail of humanitarian efforts championing the rights and freedoms of everyone.

Good reading.

—The Editors