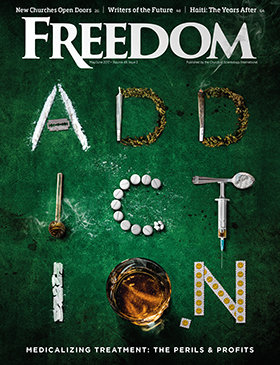

The drug dealer did not first meet the woman in an alley or on a street corner but in a doctor’s office. The narcotic poison she ingested did not come from a drug “cartel” but from chemists in lab coats and bosses in tailored suits who work for a respectable pharmaceutical outfit, a corporation that ostensibly sells “medicine.” A few years after she visited the doctor, the woman who once considered herself a “typical soccer mom” sat on Sixth Avenue in Midtown Manhattan holding a sign that let passers-by know she was embarrassed to be panhandling.

A doctor years ago had given her a prescription for an opioid painkiller after she injured herself. She quickly developed a tolerance that required her to take more pills to ease her pain. That tolerance became an addiction, then doctors refused to prescribe more pills. She turned to heroin, and although she did not consider herself lucky on that March day—her first one panhandling—she had beaten the odds by securing a bed in a shelter and a spot in a methadone program.

A few blocks south, a man in his early 20s who arrived at a Narcotics Anonymous meeting carrying a skateboard, said he started experimenting with OxyContin and other prescription opioids at high school parties, then eventually became addicted to heroin. He considered himself lucky because his parents had the wherewithal to put him in a rehab program.

An hour north by train in Stamford, Connecticut, drug addicts arrive early each morning at Liberation House to receive methadone, a drug given once daily to opioid addicts so they can function in a manner that vaguely resembles the lives of non-addicts.

Liberation House sits less than half a mile from the headquarters of Purdue Pharma LP, the maker of OxyContin. A construction worker sitting across from Purdue headquarters said, “I lost a lot of friends to heroin. And the kids today think these pills are safe because you don’t have to shoot them and because doctors prescribe them.”

A customer in a nearby Starbucks said everyone he knows has been affected by the current Oxy-heroin epidemic. Then he mentioned three of his relatives who had snorted and injected their way to shattered lives. A Stamford doctor holding a venti latte revealed that he regularly has to deny prescriptions to addicts seeking painkillers. Said Captain Richard Conklin, who heads the Stamford Police Department’s Criminal Bureau of Investigations: “What we’ve seen hasn’t been an increase in heroin use—it’s been an explosion.”

All of these people are connected through Arthur, Mortimer and Raymond Sackler, though the names were not familiar to them. The Sackler family name adorns universities, medical facilities and museums, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. The Sackler Wing in the Met contains the Egyptian Temple of Dendur, an impressive and popular exhibit that was teeming with school kids and international tourists on a Monday in March. None of the people interviewed knew that the Sacklers owned Purdue Pharma and, therefore, helped to create the prescription painkiller and heroin epidemic that is killing more Americans annually than car crashes are.

THE HORRORS OF OPIUM

Prescription opioids are painkillers derived from opium, which comes from poppies, and the chemical composition of these pills is nearly identical to morphine and heroin, a morphine derivative. In users, these drugs flood the opioid receptors in the brain that normally are activated by neurotransmitters called endorphins. All of these drugs reduce pain and create a euphoric feeling, but the extended use of any of them can build a tolerance and create a physical dependence, addicting some users.

Symptoms of withdrawal—profuse sweating, physical pain, anxiety and depression—will set in when addicts do not get their fixes. To avoid these symptoms, users take ever-increasing doses of opioids, putting them at risk of respiratory depression—slowed breathing—which can kill them. The fear of going through withdrawal can be so great that addicts will often do anything to get their next fixes. Addicts seeking prescription opioids have murdered numerous pharmacists and pharmacy customers in the last few years.

The world has known about the deadly dangers of opium—and the profits the drug can generate—for centuries. Hundreds of thousands of people have died from using opium or its derivatives, or have been killed in battles to control their distribution, and countries have gone to war over the drug. So many soldiers in the Civil War were hooked on morphine that the addiction was called “Soldiers Disease,” and movies such as “The French Connection” and “Serpico” showed the damage heroin did in New York City in the 1970s.

In other words, anyone who claims opioids are non-addictive is either willfully manipulating the truth or is stupid, and the three Sackler brothers, all of whom were psychiatrists, were not known to be stupid (see following story).

THE CURRENT EPIDEMIC

A report by the National Institute of Drug Abuse presented to the Senate Caucus on International Narcotics Control in 2014 stated: “The number of prescriptions for opioids (like hydrocodone and oxycodone products) have escalated from around 76 million in 1991 to nearly 207 million in 2013.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) said the current crisis is the “worst drug overdose epidemic in [U.S.] history,” worse in terms of deaths than the heroin crisis of the 1970s and the cocaine and crack epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s combined. In regard to prescription opioids, the CDC has said, each day “almost 7,000 people are treated in emergency departments for using these drugs in a manner other than as directed. People who take prescription painkillers can become addicted with just one prescription. Once addicted, it can be hard to stop.”

“…on these really high-dosage pills, just taking one extra pill could end your life.”

Nearly two million Americans abused prescription painkillers in 2013, and 28,648 people died in the nation from opioids in 2014. Deaths caused by heroin, according to the CDC, nearly quadrupled between 2002 and 2013. According to the National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 467,000 Americans are addicted to heroin.

“When I first started in law enforcement, heroin was more of a…low-economic type of drug,” said Conklin of the Stamford police. “You would get it a lot in the projects. It wasn’t a middle-class drug. It’s become a middle- and upper-class drug.”

The prevailing perception of drug addicts does not generally include soccer moms, college students, the affluent and the elderly, yet today’s addicts frequent malls, schools, country clubs and retirement communities.

CDC Director Dr. Thomas Frieden told CNN why he thought heroin use is on the rise. “First, more and more people are susceptible to heroin because they have been prescribed prescription opiates, like OxyContin. And the second reason is that heroin itself seems to be cheaper and more widely available.”

A CDC report titled “Vital Signs” showed that people addicted to prescription opioids are 40 times more likely than the average person to be addicted to heroin. Various studies have shown that 90 percent of new heroin users made their way to heroin via prescription opioids, and 90 percent of those users are white.

OXY IS KING

Although doctors prescribing Vicodin, Percocet, Percodan and other opioids have contributed to the current opioid addictions, Purdue Pharma, the pushers of Oxy, as the drug is known on the street, fostered the epidemic.

Dr. Andrew Kolodny, co-founder of Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing and chief medical officer for the Phoenix House treatment centers, told Freedom that Purdue intentionally minimized the impact of opioids in an “education” blitz that involved 20,000 programs aimed at the medical establishment. Purdue “wanted the medical community to feel comfortable with opioids as a class of drugs,” Kolodny said. “They weren’t talking about OxyContin. It was all unbranded. They were talking about opioids as a class of drugs. The medical community started to hear that the risk of addiction to opioids had been overblown. … [The Purdue presenters were saying,] ‘For any complaints of pain, opioids should be given. If you are an enlightened, caring doctor, you will be different from doctors who have been allowing patients to suffer needlessly.’ All of that was unbranded.” As a result, prescriptions for all opioids skyrocketed.

OxyContin, which has as its active ingredient oxycodone, derived from a byproduct of the opium poppy called thebaine, was first developed in 1916. But the timed-release formulation created by Purdue Pharma and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) that hit the market in 1996 is what led eventually to $3.1 billion in annual sales of OxyContin.

Barry Meier, author of the book Pain Killer: A “Wonder” Drug’s Trail of Addiction and Death, said in a PBS “Frontline” episode called “Chasing Heroin,” “There is no question that the marketing of OxyContin was the most aggressive marketing of a narcotic drug ever undertaken by a pharmaceutical producer.”

According to a report put out in 2003 by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), “Purdue distributed several types of branded promotional items to health care practitioners. Among these items were OxyContin fishing hats, stuffed plush toys, coffee mugs with heat activated messages, music compact discs, [and] luggage tags.”

The company held 40 “pain conferences” from 1995 to 2000 for primary-care physicians—who are not generally trained in pain management or addiction—and for doctors specializing in cancer care, and Purdue paid more than 2,500 doctors to give presentations and speeches. The company funded organizations such as the American Pain Foundation and the National Foundation for the Treatment of Pain, which rated doctors on their willingness to treat pain and stated that doctors were significantly under-prescribing opioids.

As drug dealers do, Purdue gave away its product to first-time users by handing coupons for a free Oxy prescription to physicians, who gave them to patients, who redeemed them at participating pharmacies. As many as 34,000 coupons were redeemed. The advertising assault worked, because according to the GAO report, OxyContin sales shot up from $44 million in 1996 to $1.5 billion in 2002, with 7.2 million prescriptions filled. In his book Dreamland, Sam Quinones wrote, “the bonuses to Purdue salespeople … had little relation to those paid to most U.S. drug companies. They bore instead a striking similarity to the kinds of profits made in the drug underworld.”

Purdue’s application to the FDA, which rejects or approves requests by pharmaceutical companies to bring drugs to market, stated that because OxyContin featured a timed-release element, the drug’s effects lasted for 12 hours, significantly longer than other painkillers, and this feature might make the drug less addictive because it doled out the active ingredient slowly. Meier said in “Chasing Heroin,” “There was absolutely no science to support this idea. Zero.”

In 1995, the FDA approved OxyContin in 10, 20 and 40 mg pills, then later approved 80 and 160 mg dosages, a tacit acknowledgement that patients taking the drug would eventually require larger dosages. The CDC recommends that patients do not take more than the equivalent of 90 mg of morphine per day because the risks of becoming addicted and dying from an overdose increase dramatically at higher dosages, according to Kolodny. OxyContin is more potent than morphine, so taking an 80 mg pill twice a day means “you’re on 240 mg of morphine,” Kolodny said.

The risk to seniors and people with faulty short-term memories taking large dosages of OxyContin is particularly high. “Let’s say they forget they’ve taken their pill, and they take another pill. They’ve just doubled the dose accidentally,” Kolodny said. “There’s a really good chance that they’re not going to wake up in the morning. And it won’t be counted as an overdose death. … If that patient had been on Percocet, and they accidentally took an extra pill, it’s not going to hurt them, but on these really high-dosage pills, just taking one extra pill could end your life.”

The Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act that the FDA uses to accept or reject pharmaceutical companies’ petitions states that companies can only promote products in which the benefits outweigh the risks. Kolodny said, “If that law had been properly applied, Purdue would have been permitted to promote OxyContin for end-of-life care … [where] the benefits of taking OxyContin would outweigh the risks. That’s not true when it’s prescribed for low-back pain or chronic headaches, and so the FDA should not have allowed it, but they did.”

Not only did the FDA approve OxyContin, but the agency also allowed Purdue to state on the label that OxyContin had a lower potential for abuse than other oxycodone products, a claim no other manufacturer of a Schedule II narcotic ever received from the FDA. Dr. Curtis Wright, the FDA examiner who supervised the agency’s team that reviewed Purdue’s OxyContin application, later left the FDA for a job with Purdue.

That fewer than one percent of patients would become addicted to its flagship product became the rallying cry of Purdue’s media onslaught. A former Purdue sales manager, William Gergely, told the South Florida Sun-Sentinel in 2003, “They told us to say things like it is ‘virtually’ non-addicting. … You’d tell the doctor there is a study, but you wouldn’t show it to him.”

According to Meier’s book Pain Killer, “There was nothing in the reports, either individually or collectively, to suggest that the long-term risks to pain patients of abuse and addiction from narcotics like OxyContin were ‘less than one percent.’ In fact, the studies had nothing to do with the risks of the long-term use of narcotics for chronic pain.”

If a company is willing to cite irrelevant studies to support its sales pitch, then all of its claims become suspect, particularly the one that said OxyContin didn’t appeal to addicts because the timed-release element thwarted them from getting high. Addicts simply had to moisten the coating then crush the tablets so they could snort or inject the drug.

The OxyContin label, in fact, warned users not to crush the pill, yet Purdue officials repeatedly denied in sworn testimonies in the growing number of lawsuits against the company, and in numerous interviews, any knowledge of Oxy’s extensive abuse by addicts. The officials made this claim despite doctors across the country being arrested for dispensing enormous amounts of Oxy in what are known as pill mills. Examples included a Purdue sales rep in Florida telling his superiors he had heard that Oxy was being abused and a California doctor being charged with murder in the deaths of patients to whom he had prescribed Oxy.

Purdue could have gotten away with its deny-deny-deny approach had the company not known from the beginning that its timed-release Oxy could be easily undone. Purdue developed OxyContin when its patent for MS-Contin was about to expire. Testifying before a congressional subcommittee in 2001, Dr. Paul Goldenheim, Purdue’s medical director at the time, said in written testimony, “In some 17 years of marketing MS-Contin tablets, a controlled-release form of morphine—a powerful opioid analgesic related to oxycodone—Purdue was aware of no unusual experience of abuse or diversion,” according to Pain Killer. “Purdue had no reason to expect otherwise with OxyContin.”

However, “Canadian researchers reported [in the Journal of the Canadian Medical Association] that MS-Contin turned up frequently in the black market, commanding the highest street price of any prescription narcotic. Intravenous drug users scraped off the outer coating of MS-Contin tablets to circumvent the timed-release mechanism before crushing and dissolving the pill and then injecting it to get a heroin-like high,” according to Pain Killer. And Oxy “created addicts, not just among those who looked to abuse it,” according to Dreamland, “but among many looking for pain relief. Every patient who was prescribed the drug stood a chance of soon needing it every day.”

A SLAP ON THE WRIST

As addiction clinics, methadone centers, emergency rooms and morgues filled up and the number of lawsuits against the company mounted, Purdue continued its deception campaign and hired high-powered law firms and public relations agencies. Though focus groups in 1995 showed physicians were worried about Oxy’s abuse potential, and despite senior company executives being fully aware of the drug’s addictive properties—as revealed in internal Purdue emails from 1997 that were eventually revealed in court discovery—Purdue kept up its charade while raking in profits.

In 1998, Purdue sent physicians promotional videos that made “unsubstantiated claims minimizing the dangers” of OxyContin without having had the video approved by the FDA, according to the GAO report. And in 2001, the company sent physicians a separate video that made unsubstantiated claims about OxyContin users’ “quality of life and ability to perform daily activities.”

“…we were finding people all over the place—public restrooms, cars—with the needles still in their arms.”

In May 2001, the DEA took unprecedented action by launching a campaign to reduce OxyContin use, specifically naming the drug. In July 2001, at the FDA’s behest, Purdue agreed to remove the claim on the OxyContin label that said the timed-release element may reduce addiction risk. In 2002, the FDA cited Purdue for overstating in print advertising that OxyContin is safe.

In 2007, after more than a decade of lying for the sake of profits, ruining countless lives, Purdue and three of its executives pleaded guilty in federal court to charges of “felony misbranding of a drug, with the intent to defraud and mislead.” In total, the company paid $634.5 million in fines (a drop in the bucket compared to the estimated $35 billion OxyContin has generated), and no one went to prison. In fact, Oxy profits tripled from 2007 to 2010.

THE MORE THINGS CHANGE…

Purdue claims it was first alerted to people abusing Oxy in 2000, yet the company took 10 years to reformulate the drug, theoretically making the pills less abuse-prone—and did so only after it had been fined.

The overprescribing of painkillers by unscrupulous doctors led to a federal crackdown on pill mills, which catalyzed heroin use as the drug became far easier and far cheaper to obtain than prescription opioids.

The purity of heroin has increased from a customary 6 to 12 percent pure to 80 to 90 percent. Drug dealers are cutting it with fentanyl, which is about 100 times as powerful as heroin, so addicts are being blindsided.

“You’re doing 10 bags at 6 percent purity, and now you’re doing 10 bags at 80 percent purity—it’s lights out,” Conklin said. “For a while we were finding people all over the place—public restrooms, cars—with needles still in their arms.”

Addiction to painkillers and heroin has obviously hurt and killed tens of thousands of people, but the family that wholly owns Purdue Pharma, the Sacklers, is doing just fine, having amassed a fortune of $14 billion, according to Forbes. Though Arthur and Mortimer have died, Raymond and various descendants continue to reap the enormous profits generated by OxyContin.

To slow down the opioid epidemic, Conklin and Kolodny believe the country must use a multi-pronged approach. “This is something we’re not going to arrest our way out of,” Conklin said. “You have to prevent people from getting addicted in the first place,” Kolodny said, “and that boils down to getting doctors and dentists to prescribe much more cautiously. And it means education that explicitly corrects the misinformation that Purdue and other opioid makers promulgated.”

Many factors contributed to the raging epidemic. The solution, according to the FDA, “requires coordination and commitment from across federal, state and local partners, including prescribers.” Further, said the FDA, while it’s doing “everything possible to combat this devastating epidemic of opioid dependence,” the agency will “re-examine the risk-benefit paradigm for opioids and ensure that the agency considers their wider public health effects.”

A QUESTION WORTH ASKING

In 2011, Alan Must, Purdue’s vice-president of state government and public affairs, told Fortune magazine, “Obviously, the idea that our business model is based on getting patients addicted and dependent is absurd.”

But isn’t that the goal of every drug dealer? Arthur Sackler’s history of unethical advertising, the misinformation having been disseminated by Purdue Pharma for decades and the billions of dollars those lies generated at the expense of the hundreds of thousands of people who have become addicted to OxyContin and heroin—many of whom died or will do so soon because of their addictions—raise a question. On the original OxyContin bottle, it said, “Swallowing broken, chewed, or crushed OxyContin tablets could lead to the rapid release and absorption of a potentially toxic dose of oxycodone.” Was this meant as a warning or a suggestion?