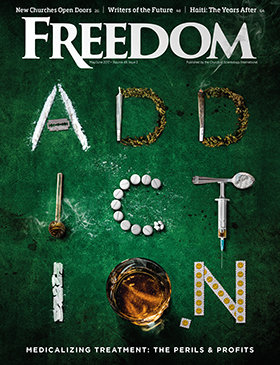

You may not have noticed, but the War on drugs is over. Who won the war? You will be surprised to learn that it wasn’t even one of the combatants.

Really, it was never close. The U.S. government, with its unlimited financial, legal and military resources, never had a chance. The cartels, which seemed unstoppable based on an early lead and billions of dollars in profit, have been shown up as amateurs. The winners are the media, but they couldn’t have done it without a major assist from their brother-in-arms, the pharmaceutical industry.

You know about the crack houses where addicts congregate to sell their jewelry, their bodies and anything else they can monetize for drugs. You know about the meth houses with their chemical fires, rotted teeth and ruined lives enslaved by the search for the next fix. You know about the homeless veterans begging for change on freeway on-ramps. And you know about the careless teens who allowed peer pressure to set them on the path to perdition. Reading this issue of Freedom, you’re also learning that over-prescribing and off-label prescribing of painkiller OxyContin has led to the heroin addiction that, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics, is killing nearly 80 Americans every day.

But the media? How did the media get addicted to drugs?

To find the answer, all we have to do is remember what we learned from the Watergate scandal and All The President’s Men, the book by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein. It taught us to follow the money.

Historically, Big Pharma was not allowed to advertise prescription medicines on radio or TV. Companies knew that when they advertised over-the-counter remedies like aspirin and nasal spray, sales increased. And neither they nor the broadcasting industry liked the rules that kept pitches for prescription drugs off the air.

Deadly Duo: PHARMA + MEDIA Drug ads in the mass media were illegal 20 years ago. Thanks to the media and Big Pharma, they are ubiquitous.

A certain wisdom prevailed within the government agencies that birddog the industries in question. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA), which is charged with protecting consumers from dangerous drugs, didn’t move quickly in the serious business of approving new forms of advertising individual drugs or classes of drugs.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC), responsible for truth in advertising, was duly skeptical on the question of whether consumers could get enough information about powerful new drugs in the relatively short amounts of time allotted to typical commercial messages. There’s a continuing cat-and-mouse game going on between the regulators and industry: 11 of the major pharmaceutical companies agreed to pay over $13 billion in fines since 2009 for illegal promotion of drugs. Yet pharmaceutical advertising remains the fastest-growing advertising market, according to Standard Media Index (SMI), representing 7 percent of total U.S. advertising dollars in the third quarter last year.

The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) sets policy for the use of our common, invisible asset, the electromagnetic spectrum, upon which ride the over-the-air signals of radio and television stations. That agency had an obligation to ensure those airwaves—lent to broadcasters with the understanding that they would use them “in the public interest“—were in fact hewing to that mandate.

The status quo was conservative. Slow and steady ruled the day. Then came the anything-goes 1980s, when we were taught, by elected officials, ironically, that government, long regarded as the helpful friend of the ordinary citizen, was actually the all-purpose villain in civic affairs. President Reagan even told us government was the problem, not the solution, with his cleverly cynical aphorism about being wary of the civil servant who intones, “I’m from the government, and I’m here to help.” The ’80s flipped the proposition that government was, in President Lincoln’s words, of, by and for the people. It is clear in retrospect that with increasing frequency, government was of, by and for Big Business.

A subtle shift in governing priorities had begun. Regulators were pressured to let businesses have considerably more leeway. The FTC stopped hounding makers of miracle cures, and all types of unproven remedies showed up in supermarkets and health-food stores.

The FCC, under increasing pressure from Congress and a monied, influential lobby, the National Association of Broadcasters (NAB), rolled back 50 years of rules that demanded the broadcast industry consists primarily of locally focused companies that could own only one station per service (AM, FM, TV) per market. The result: Companies could own just about as many stations in as many markets as they could afford, effectively shrinking the industry from hundreds of local operators to just a handful of powerful conglomerates that spoke with one voice—the NAB’s—on the subject of commercial content.

Breaking the Dam

The FDA, perhaps even more than its counterparts at FTC and FCC, felt the pressure from Congress and PhRMA, the pharmaceutical industry’s powerful lobby.

The “direct-to-consumers” dam broke for real in 1997 when the FDA finally relented and eased up on the pharmaceutical companies. Since then, according to the New England Journal of Medicine, spending on these ads has quadrupled. A 1999 study published in the Journal of General Internal Medicine said one-third of survey respondents proactively approached their doctors about the brand-name drugs they’d seen advertised, and fully a fifth requested a prescription. In many of these cases, a less expensive generic was available. Doctors are only human, and when, according to a study in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), patients asked for a drug by name, doctors were more likely to prescribe it than simply writing a prescription for the generic equivalent.

The tension between industry and regulators is not a new thing. In the 1950s, the Senate Anti-Trust and Monopoly subcommittee expressed its frustration with the pharmaceutical industry when the committee’s chair, Sen. Estes Kefauver (D-TN), publicly rebuked Big Pharma for foisting high-priced patented medicines on patients. He also emphasized that marketing expenses are passed along to consumers and that generally the new drugs were no more effective than the off-patent ones they replaced.

$57.5 billion dollars, the total expenditure by the U.S. pharmaceutical industry on promotional activities in a single year compared to $31.5 billion on R&D.

In a high-tech age in which pharmaceutical research and development, never an inexpensive process, was having frequent breakthroughs, the pharmaceutical houses and the broadcasters were losing a lot of money by not being able to advertise the fruits of their pricey, patent-protected labor.

The onslaught began in the 1990s with patented drugs that had a fairly broad appeal. Newly patented derivatives of tranquilizers like Valium—which made its first appearance in the mass market propelled by the popular 1960s novel The Valley of the Dolls—got a lot of exposure.

Many of the drugs developed by 2000 had limited application but could be marketed at high prices and produced large profits. Most addressed ailments present in a tiny fraction of the population, numbers so small that the drugs formerly would not have justified mass marketing on broadcast television. The patent process, however, combined with high-powered marketing operations, gave the pharmaceutical companies the ability to price these new drugs at levels that heretofore would have been usurious.

The companies argued that the only way to continue the costly R&D efforts for these micro-targeted miracle drugs was to get them directly in front of potential patients, a practice frowned upon by the American Medical Association (AMA).

Thus a two-step strategy was born: First, saturate the airwaves with all manner of patented designer drugs. Second, use a combination of sales force and incentive trips and speeches to entice willing physicians to prescribe these new, expensive drugs, the AMA be damned.

Enticing the Doctors

Big Pharma markets to physicians in ways both subtle and not. Brigades of great-looking young women roll their attachés full of new meds, pre-filled prescription pads, golf balls and tickets to exotic locales into doctors’ offices. The doctors start prescribing the new drugs. They are rewarded with sweet come-ons to exotic golf and vacation destinations. Sure, there’s always a legit-seeming speaker and probably even Continuing Medical Education (CME) credits that all doctors need to remain legal and current in a fast-changing world. Soon enough, the slower adopters stopped fighting the irresistible tug of blanket television advertising, sophisticated Pharma reps and the incentives they offered (anyone for a few days on the French Riviera?), and patients who were once given low-cost generics were now demanding and receiving high-priced designer drugs. Neither doctors nor patients complained because insurance companies were footing the bill.

The result was that suddenly natural aspects of aging were diseases for which we needed prescription drugs. Aren’t hair loss and joint pain conditions that can be “cured” with a hat and an aspirin?

The Result

Now drug advertisements are so commonplace, we hardly think about how they have infiltrated our daily routines. The commercials during the evening news now feature the latest, pricey drugs, invented to supplant the generics that no longer make Big Pharma rich. They advertise cures for ailments we didn’t know we had or had previously managed to endure without too much medical assistance.

Now drug advertisements are so commonplace, we hardly think about how they have infiltrated our daily routines. The commercials during the evening news now feature the latest, pricey drugs, invented to supplant the generics that no longer make Big Pharma rich.

For instance, Jublia, the new toenail-fungus medicine advertised frequently on television, costs thousands of dollars for a complete course of treatment, which according to The New York Times, is effective only 20 percent of the time. That’s a stunning waste of money.

The debate among health care professionals, especially medical ethicists, rages. New Zealand is the only other nation that allows prescription drug advertising.

Do we really want or need a culture of self-diagnoses in which unqualified amateurs—patients like you and me—see their previously unknown or unrecognized health deficits on TV and tramp off to the doctor demanding new, expensive, heavily advertised, potentially dangerous drugs?

Have you listened to the disclaimers? They’re often longer than the sales pitches. I think I’d take my chances swimming with the crocs in the Nile before I’d take some of this stuff.

Pharma would have us believe that R&D spending is so high that all the industry needs to do to recoup its investments is to sell these new drugs at eyebrow-raising prices. The truth is their marketing costs vastly outstrip the costs of bringing new drugs to market. The January 4, 2008, edition of “Fierce Biotech,” a daily industry newsletter, compared the total dollars the U.S. pharmaceutical industry spent on R&D—$31.5 billion—with the total expenditure that U.S. drug companies made on promotional activities, which was $57.5 billion. That number includes education, trips, meals and sales calls. Because these figures were published in 2004, it is safe to assume those numbers have risen, as a casual glance at the TV will show. Direct-to-consumer advertising alone accounted for $4.8 billion of Pharma advertising in 2015, up a staggering 20 percent since 2011. As if that’s not a fast enough increase, Standard Media Index says Pharma advertising increased 41 percent from 2014 to 2015—the largest increase of any category of advertising. This new arrangement plays a big part in the breakneck inflation rate of health care costs.

For now, the media and Big Pharma have won this battle—but not the war. Shout out to FTC, FDA and FCC to stop pharmaceutical advertising—now! One way to be heard is to write: letters@freedommag.org. Freedom, its readers and an army of concerned citizens can make the federal agencies listen.