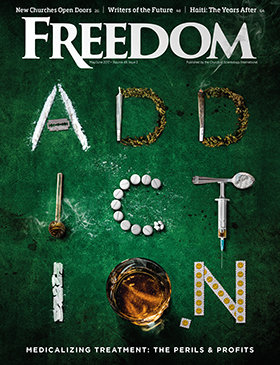

In the land of the opioid epidemic, foreign websites and credit cards deliver potent painkillers without prescription to America’s heartland.

In the 12 months I researched these stories, I interviewed dozens of current and recovering opioid addicts, in person, on the phone and via email and social media. Most were strangers—though once word spread that I was reporting on the opioid crisis, private messages came in from friends as well.

I heard from two—one East Coast, one West Coast—each who knew loving middle-age mothers who lost adult sons to opioids. I heard from a Tennessee woman I knew whose teenage daughter had been in and out of rehab three times. I talked to her daughter as well, and she told me she was now clean—except for drinking, and occasionally smoking pot. “I’ve got this,” she said.

But I hung up the phone fearing that she wasn’t through shooting heroin, and a few months later I learned that she had overdosed—and been saved by paramedics with a dose of the overdose antidote naloxone.

Many I spoke with started their opioid journey with prescribed pain pills. Some would later leave their nice houses and find street drugs in back alleys and parts of town they never would have ventured before to feed their addiction. I rode with police officers who showed me those neighborhoods, who told me the only reason people came there was to get drugs.

Then the circles got closer. I talked to a relative, a pain medicine specialist, who described how he had been offered “rewards” for prescribing opioids for normal pain—which he said he declined to do.

As this issue was about to go to press, I learned that a friend, a 57-year-old production designer for film and commercials, had just died, from a heroin overdose. Our kids are the same age—he and I coached Little League together. We hung out at the field with our kids countless times, bonding over the joy we took in trying to teach and protect our sons. His ex-wife found him alone at his home, on her birthday. The pain is unfathomable.

At his memorial service, his two sons, a nephew and another relative performed one of his favorite songs, Pink Floyd’s “Wish You Were Here.”

When I told another friend how he had died, she was dumbfounded. “Wait, the guy that coached my kids, who has two sons, and a job … what, he comes home and does heroin? Who does that?”

More people than you know.

There were other degrees of nonseparation. Another friend, a parent of three that I had known for years, sent a private message that she knew someone I should talk to: her. Her kids went to the same religious school my kids went to. I had served on committees with her and her husband. They were your average American middle class couple. I had left my kid at their house for play dates and sleepovers.

But they too had been addicts, she told me. They were clean now, but had suffered through opioid addiction that lasted more than five years. Tramadol, she said, a supposedly harmless opioid-based pain medication, started as an innocent option and became an addiction costing thousands of dollars, the respect of a child and their home. “It was supposed to be nonaddictive—that’s bullsh**,” she said. “Had I known, I would never have started that.”

Neither would they have likely been able to fuel their tragic habit, except for a reality that postal inspectors and law enforcement officials have described to Congress as a river of illegal prescription drugs flowing into the country. My friends didn’t have to go to the bad part of town, to the other side of the tracks, to drug houses or pill mills.

They had them delivered by U.S. Mail and FedEx. To their door.

And so, I did too.

My friends didn’t have to go to the bad part of town, to the other side of the tracks, to drug houses or pill mills. They had them delivered by U.S. Mail and FedEx. To their door.

The India Connection

Earlier this year, a U.S. Senate committee detailed the ease with which investigators were able to access online, highly addictive opioids like fentanyl and carfentanyl. Starting with a Google search, “fentanyl for sale,” they contacted sellers in China willing to sell bulk quantities of the synthetic opioid. Preferred payments were in Bitcoin or through PayPal. The committee reported that nearly $800 million worth of illicit fentanyl doses had been sold online to U.S. consumers from China in the past two years.

The bipartisan report by the Senate Homeland Security Committee said that while commercial shippers like FedEx and UPS are required to supply Customs and Border Protection with advance data about international packages, drug organizations continue to use the two corporate shippers to slip packages in. Further, advance documentation on packages is not required for U.S. Postal Service deliveries received from foreign postal organizations. Those packages are theoretically inspected manually upon arrival in the U.S. Yet as one U.S. postmaster told me, there are few specific inspection rules, at least at the local level. “The message is more about keeping yourself and your family healthy,” he said.

Despite government and industry efforts to control opioid abuse and addiction by tightening prescription access and making it harder to convert pharmaceuticals for street use, the tap on illegal drugs has apparently, been running wide-open on the internet all the while. I decided to try it.

Iodine, a blog site that reports on information from the Food and Drug Administration and the National Institutes of Health, recently called Tramadol “the most dangerous drug in the world.” Introduced in 1995, this synthetic opioid—similar to OxyContin—carried with it the promise of low risk for addiction, a promise that has proven false. Tramadol has been widely prescribed in the U.S., despite its great potential for both addiction and abuse. Prescriptions here rose by 88 percent from 2008-2013, from just over 23 million prescriptions to nearly 44 million.

“One of the reason[s] people like taking Tramadol,” Iodine reported, “is because for some people it works as an antidepressant, producing euphoria or energy, unlike other opioids which tend to make people drowsy. This has led [to] it being used recreationally, while people still go to work or live their daily lives.”

Studies show the drug being abused worldwide, with significant occurrences from the African nations of Cameroon, Nigeria and Egypt, to Ireland and more. SAMHSA (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration) reported a 145 percent increase in Tramadol-related adverse reactions from 2005-2009, at a level that continued for at least two years.

It Started Quickly

Paula (not her real name) said that after a particularly stressful week involving school bullying, a restraining order and other anxieties, her husband suggested she take one of his pain pills, which he’d been taking for years, first prescribed for a skin condition. He thought it would help her relax, as most opioids do.

Instead, “It felt like an upper to me,” she recalled. “I started taking them more and more. I started losing weight. It gave me so much energy. Before I knew it, I was full-on addicted.”

Her husband had been refilling his prescription from an online pharmacy—one that never asked questions. So when Paula wanted some of her own, she just ordered them.

“We Googled it and looked at the top one or two names.” They called, or sometimes ordered online, and were never asked for a prescription, or a doctor’s name—just a credit card number. While they were told they were talking to a Canadian pharmacy, the guy on the phone usually sounded like he was from India, she said.

“And we were just blowing money. … But I just needed more pills,” she said. “Each bottle of 80 pills was like $120, or $220, I don’t remember,” she said. Between the two of them, they were ordering two bottles a week. “We blew the college money for one of [the kids],” she said.

“The deliveries came so often, I became friends with the FedEx guy,” she said.

She and her husband shared their addiction. As costs mounted they tried to stop. Eventually the narcotics deliveries led to financial ruin.

“There’s no more pills, we have no more money, that’s it, you’re off of it. I probably would have kept going if we could have afforded to,” Paula said.

She quit cold turkey. She described the experience as hellish. Her husband’s was worse, because he tried to wean himself with Suboxone, a lower dose opioid that supposedly eases withdrawal from stronger opioids.

Three weeks later, a plain padded 5x9-inch envelope from Singapore showed up in my mailbox. … It’s that easy. No prescription, no doctor identified, no proof of any condition or identification.

It took Paula a month to begin to feel normal, she said, but her husband found it was harder to kick Suboxone than the opiate. It took him months to finally get rid of all the symptoms.

“We had to sell the house,” she said. “It was bad.”

Canadian Pharmacy’s website is adorned with half of the Canadian flag. Nowhere on the site does it say they’re in Canada. In the FAQ section, it says they manufacture and ship from India.

I Googled “opioids online” and found a few options. I decided to go with the one I at least had a referral from, Canadian Pharmacy. The site listed dozens of drugs sold, alphabetically by categories, from Allergies, Anti-Anxiety and Antidepressants, lots of options for men’s health, all the way through the alphabet to Weight Loss and Women’s Health. In the middle was Pain Relief.

Under that heading were options of Elavil (an antidepressant with the potential for a fatal overdose); Modafinil (a Schedule IV controlled substance similar to an amphetamine); Prednisone (a steroid used to manage inflammation); and Soma (a muscle relaxer that blocks sensations between the nerves and the brain).

All of these require a prescription in the U.S., which disclose potential side effects, and some are known to be potentially addictive. At the bottom of the list was Tramadol, which the site described as “a strong opioid analgesic sold within the territory of the USA under the brand name Ultram.”

Tramadol is available on the site in dosages of 50, 100, 200 and 250 mg. I ordered 30 pills at 100 mg, with regular delivery. My total charge was $97.13, and I was promised a delivery in two to three weeks. The website’s FAQ said the drugs were generic but with the same quality control as brand-name, and that “they are approved by the Indian FDA, as that’s where they are manufactured and shipped from.”

And three weeks later, a plain padded 5x9-inch envelope from Singapore showed up in my mailbox. Inside were three sets of 10 white pills, professionally packaged, with “Tramadol” stamped on the back, along with a manufactured date of four months before, and an expiration date of almost seven years later. It read “Manufactured in India by HAB Pharmaceuticals & Research Limited.”

It’s that easy. No prescription, no doctor identified, no proof of any condition or identification.

I called the company on an 800 number for U.S. residents to ask how they were able to distribute narcotics that, to be legal, require a prescription in the United States. A woman who identified herself as Keisha told me, “In India, opioids are not considered controlled substances.”

It’s been years since Paula and her husband quit. But temptation still arrives frequently in the mailbox.

“I’m still getting refill emails,” she said. “I’m like, ‘Oh God.’”