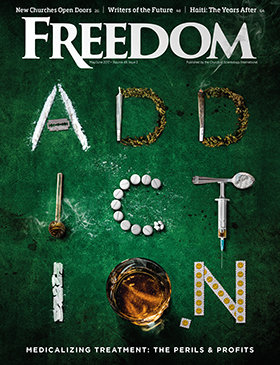

U.S. opioid epidemic did not happen overnight; crisis warnings by Freedom three decades ago largely ignored by pharma-friendly mass media.

In May 1987, more than 30 years ago, Freedom magazine published a story alerting its readers to a growing problem in the U.S.—the cancerous spread of drug addiction that was metastasizing as an ever-increasing number of white collar professionals began shooting heroin.

“Fifteen years ago, the drug problem seemed to be confined to the dingy apartments and back alleys of the slums,” the magazine noted. “Today, drugs have moved into the family living room, becoming almost as commonplace as a television set. The drug problem has seeped into the very roots of society, but America’s drug problem did not just come about all by itself. It was caused.”

Freedom also quoted John S. Duff, co-author of the book, The Truth About Drugs, The Body, Mind and You, outlining the seemingly unlimited supply of chemicals available.

“A synthetic drug like heroin, called fentanyl, or sometimes called ‘China White’ on the street, has some 1,400 or so different chemical alterations,” Duff said, referring to the difficulty in banning any one particular compound. “You can put enough of this drug on the head of a pin to kill 50 people.”

At the time, references to “street heroin” were seeping into the cultural lexicon. But in plain terms, what young men and women were chasing was a recreational opioid high. Today, far greater numbers of men and women of all races and ages are again seeking that high—or an escape from withdrawal sickness. But more often than not, their addiction is the result of a pain pill onslaught most of America didn’t see coming—despite the warnings.

Little attention paid

Opioids like fentanyl, used as additives to “cut” pure heroin and boost its high, diminished in popularity after law enforcement agencies cracked down on junkies—so called after the euphemism for heroin—“junk”—became a popular street term.

Powerful prescription opioids, which had been on the market since the 1970s were, at the time, cautiously prescribed, and carefully dispensed—generally only for cancer patients and those in extreme pain. The caution was driven by an overwhelming belief in the medical community that opioids carried a significant risk of addiction. Thus, “lesser” pain—back issues, oral surgery, sometimes even broken bones—was usually treated with aspirin, acetaminophen, or other nonnarcotic, over-the-counter pain relief.

But in January 1980, a brief letter published in the New England Journal of Medicine, changed all that. The letter, a nonscientific opinion, based on observation and not clinical trials, suggested that hospital patients receiving such narcotics showed no signs of addiction. This opinion was trumpeted as fact by pharmaceutical companies, and heavily influenced doctors who interpreted the opinion to mean opioids were safe to prescribe to patients in pain.

Americans of every color, gender, age, education level or location, many who believed “it can’t happen to me, it can’t happen here,” have had an awakening.

Purdue Pharma was one of the first to run with that “evidence,” introducing OxyContin, a time-release pain pill. They flooded the market, using sales staffs who pushed the idea that not treating pain with this wonder drug was virtually a violation of the Hippocratic oath. Before long, pharmaceutical manufacturers and distributors were paying doctors to prescribe their opioid pain relievers, even paying them hundreds of thousands of dollars for lectures extolling their supposed benefits.

All of America, it seemed, was in pain—and with the right encouragement, doctors no longer saw pain as something to be ignored. Instead, they began to aggressively treat those symptoms with what they were told were time-release pain pills—with no significant concerns about addiction.

Following the money

Years later, in early 2016, Freedom was again writing about the opioid epidemic—by then the No. 1 cause of accidental death in the country. In the same issue, Freedom also wrote about the Sackler family, one of the leading philanthropic families in the world. Their sizable generosity—millions of dollars donated through the Sackler Trust and the Dr. Mortimer and Theresa Sackler Foundation—continues to help fund the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, The Sackler Wing at the Met, the Egyptian Temple at Dendur at the Met, the Sackler Gallery at the Smithsonian, and several other museums, universities and theaters in London.

Named in 2015 by Forbes as one of America’s wealthiest families, the Sacklers arrived at their fortune, conservatively estimated at $14 billion, from Purdue Pharma, their family pharmaceutical business.

Within the last 24 months, following a series of groundbreaking stories late in 2016 by the Charleston Gazette-Mail, every media institution in the country and many around the world have now written about the opioid epidemic. The world has learned about the aggressive sales tactics of the pharmaceutical industry, as well as the over-saturation by distributors of prescription opioids, which led to pill mills. Millions of pills were sent to pharmacies and given in prescriptions … and the avalanche of addiction followed.

Laws requiring distributors to alert the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) of unusual surges in prescriptions were not followed—laws that might have prevented the meteoric escalation of this epidemic. And while the manufacturers saw billions of dollars in revenue, the distributors may have made even more, continuously pumping pills into every corner of the country.

Americans of every color, gender, age, education level or location, many who believed “it can’t happen to me, it can’t happen here,” have had an awakening as the epidemic has infected all occupations and economic levels.

Communities, counties and states, faced with skyrocketing social costs, have turned to lawsuits against manufacturers and distributors. Cardinal Health, AmerisourceBergen and McKesson are the three biggest pharmaceutical distributors in the country. “Each of them generates over $100 billion a year,” said West Virginia attorney Paul Thomas Farrell Jr., who is suing distributors on behalf of seven counties in his state. “Each of them has climbed the Fortune 500 rankings, in direct parallel to a skyrocketing relationship to the sale of OxyContin,” he said.

Of course, manufacturers and distributors have been sued before and have paid out multimillion-dollar settlements and penalties. New litigation may potentially result in settlements in the billions of dollars. But, sadly, say critics, it may not be enough to right the wrongs. There is no putting the genie back in the bottle.

In a report released late last year, the White House Council of Economic Advisers estimates that in 2015, the economic cost of the opioid crisis was $504 billion, or 2.8 percent of GDP that year. This is over six times larger than the previously estimated economic cost of the epidemic. And it’s growing.

That was for 2015. The CDC reported the opioid overdose death rate increased nearly 28 percent in 2016, and now a new 2017 provisional report shows a further 16 percent increase. While the final statistics are still not released, based on experts’ predictions, the numbers continue to rise, as do the national costs. The questions are yet unanswered: Is one trillion dollars an unreasonable estimate as to what the opioid epidemic has cost? What will it cost to repair the social and cultural damage? And the most troubling question yet: Who will pay for that?